DP World Tour’s shift to a more centralised approach has cut emissions equivalent to powering 68 homes for a year

Standing over a tournament winning putt and capturing the moment perfectly for a discerning audience at home can result in a similar sort of pressure for both golfer and producer. Depending on the context, it could be the kind of moment that defines careers and etches itself into the memories of fans all over the world.

The optimal environment for both the individual on the green and the person in the studio is quiet. A quiet which allows for the focus needed to sink the shot or document it in a way that makes it utterly satisfying for those watching live on television.

During the production of the 2023 Open de France, David Mould found himself in such conditions. There was no hubbub from people walking around him. No constant hum of an air conditioning unit. Just the gentle murmur of colleagues going about their work.

Two days prior, the European Tour director of television had been “nervous”. After all, it was the first almost fully remote production undertaken by DP World Tour for one of its events, and there was a feeling of entering into the unknown. His finger hovered over his laptop mouse as he scoured for flights to get a crew out to Paris.

But he held firm, and his “faith in the team” paid off. After overseeing a successful transmission just over 300 miles away in London’s IMG Studios in Stockley Park, Mould came to the conclusion that being off-site and physically away from the action “didn’t actually affect” his production decision making. In fact, it was aided by a bigger, quieter workplace.

“It was peaceful and I could concentrate. Concentration is the biggest part of what we do, and being in a room which enabled that was amazing,” Mould tells The Sustainability Report. “I really don’t remember anything going wrong at all, and things are getting better each time.”

From six to 10

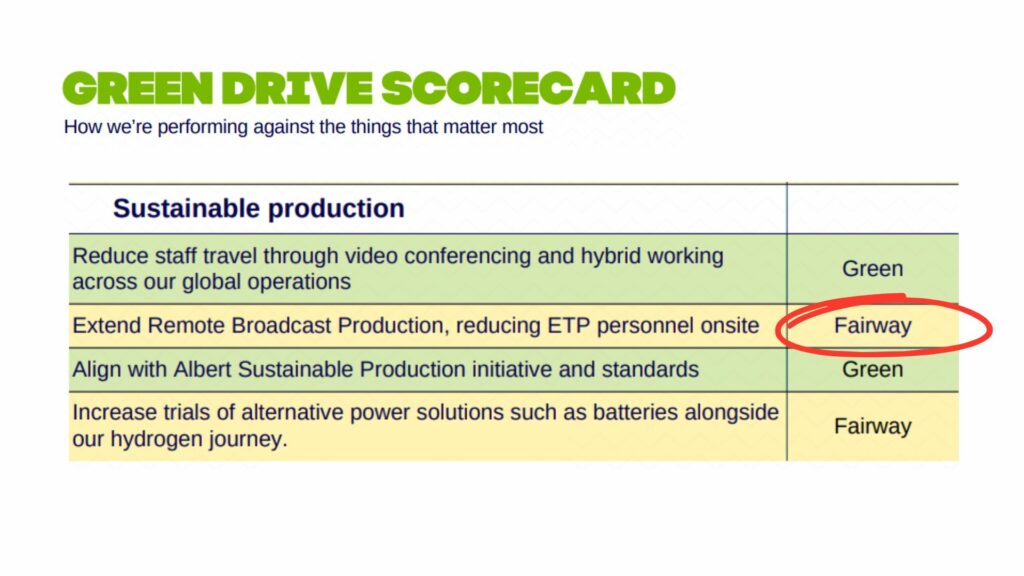

Remote production is a crucial element of the DP World Tour’s ‘Green Drive’ sustainability roadmap. Following the Open de France, a further five events were broadcast remote in 2023, saving around 522 tonnes of greenhouse gas emission (CO2e) – the equivalent of 68 homes being powered for a year or taking 124 petrol-powered cars off the road for 12 months.

That number will increase to 10 events over the 2024 season and Neill Price, operations and technical manager for European Tour Productions, hopes that will “double” every year going forward.

For its first Green Drive report, published in May 2024, the Tour analysed 10 of its events across the globe to get a snapshot of its environmental impact (there are 100 international events across Tour schedules, with around a quarter owned and controlled by the Tour). Just over 8% (approximately 658 tonnes CO2e) of the emissions calculated were related to ‘core travel and accommodation’, including that of the on-site production team.

Reducing the carbon impact of the Tour is very much the catalyst behind shifting more events from on-site to remote production. In essence, remote production involves relocating multiple production elements to a purpose-built remote hub. While engineers, directors, producers and mixers are among those centralised, some roles, such as on-screen talent, camera operators and production management, remain on-site, effectively splitting the team.

Storytelling challenge

The Tour is one of a number of sports embarking on this journey. SailGP has broadcast remotely for several years, while remote operations have helped Formula 1 reduce emissions related to its business travel.

However, the nuances of a sport like golf, which can be unpredictable in terms of the conditions and where players ultimately hit the ball, can make remote production a challenge from an editorial perspective. While bringing as many of the team into Stockley Park as possible is better for team communication, there are some grey areas over roles like match commentators, for example.

“I can tell if a commentator is not on site,” says Mould. “It’s a very hard thing to replicate for a big sporting event. Naturally, if you’re on site, adrenaline can take over and you can hear that.

“Commentary is about storytelling – they’re telling the story for the people at home. I like them to talk to the players, find the backstory, look at the greens and the fairways and the bunkers. They’re there to tell viewers about the things they can’t see.”

Connectivity, Price adds, can also be complex. Indeed, the first, most important aspect of setting up a remote production is securing a reliable connection between the resources on site and the centralised production hub. That is usually in the form of a “private fibre supply” which is strong and diverse enough to “let everybody sleep well at night”. But that can take months to secure.

The good news is that technology is making remote production much more reliable. Price explains that during an event in China a few weeks ago, latency (the delay in picture and sound) was only 420 milliseconds to London.

“It’s extraordinary,” Price adds. “When we started this journey, people were talking about latency in terms of one second plus, even two seconds. That’s a testament to the team and our providers.”

Human outcomes

Six years ago, Andrew Rundle, associate professor of epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health, wrote an article for Harvard Business Review about his research into the impact of frequent business travel on the health of the employee.

He found that those travelling 14 days or more per month were more likely to have poor physical health, clinical symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as trouble sleeping. These circumstances, Rundle deduced, could have a knock-on effect on their employers; a higher number of sick days and reduced productivity and performance.

The reduction in travel for production staff has not only been a springboard for better environmental performance, but also human outcomes, both Mould and Price agree. Talented staff members who weren’t able to travel often are no longer missing out on opportunities, and people no longer have to try to perform their best work after a long, draining flight.

“You can bring different people into the production environment that you couldn’t in the past and we can provide a much more inclusive environment,” Price says. “And, technically, there are so many other areas to exploit.”

On the latter point, Price explains that remote production opens up a number of possibilities when it comes to creating content additional to the live broadcast, including digital content, personalised content and regionalised content that couldn’t be done through a traditional on-site production setup.

“We’re never going to go back,” stressed Mould. “I think we’ve probably only realised 10% of what we can do. I really believe, without giving a timescale, that we will broadcast every event remote in the not too distant future.”

Opt into our weekly newsletter for exclusive content focused on sustainability strategy, communication and leadership for sport’s ecosystem.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *