FC Nordsjælland club director Søren Kristensen discusses the environmental and social credentials of the new Favrholm Stadionkvarter development

In the town of Farum, 20km northwest of Copenhagen, a typical weekend morning sees groups of road cyclists venture into Denmark’s wilderness. Resembling many other Danish towns of around 20,000 residents, Farum is, in fact, a multicultural hub. Many immigrants living there, the majority from Turkey and the Middle East, mean over 50 languages are spoken.

In the northwest of town, Right to Dream Park marks the extension of this cosmopolitan trend via Superliga outfit FC Nordsjælland. The Sustainability Report has previously covered why this is a club that operates differently to its peers, and to help fully actualise the Right to Dream vision, FCN are due to move their operation to ‘Favrholm Stadionkvarter’, a further 15km north near Hillerød.

What should building a sustainable, mutually dependant neighbourhood from scratch look like in modern society? Søren Kristensen, club director at FCN, is overseeing the Favrholm Stadionkvarter project with this question in mind, dreaming of the site eventually becoming a trailblazing project for future urban and residential projects in Denmark and beyond.

“This is what I get up in the morning for every day,” Kristensen beams, “building such an environment for young kids to have a future, and look into the future.”

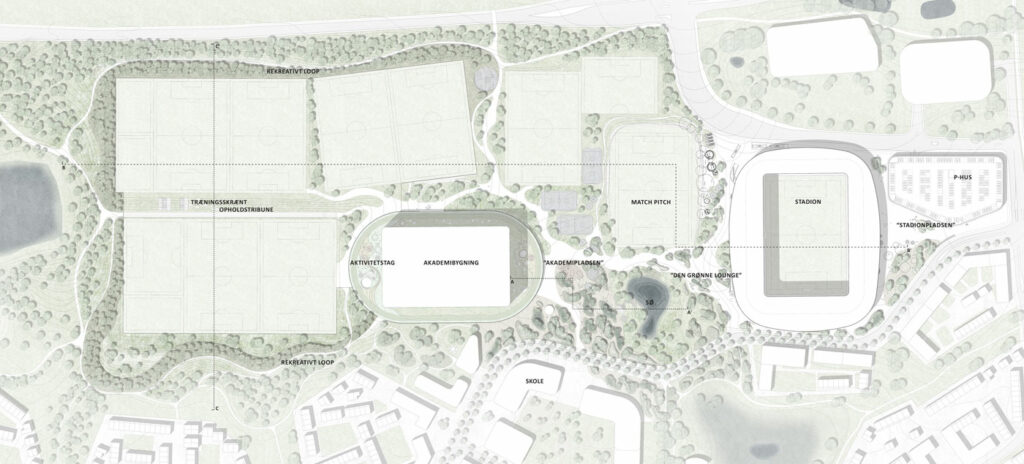

Favrholm Stadionkvarter will include a stadium, surrounding football pitches, a sports academy, 2,200 homes, businesses, a day-care centre, hospital, hotel and a school.

The new town district will be focused around the new stadium, which, along with the first houses, is expected to be completed by 2027. There will be six subsequent phases that will take an extra 8-12 years. The whole area will be built according to the DGNB (German Sustainable Building Council) standard. FCN won’t be able to achieve the highest platinum level as new buildings are required, but Kristensen notes how existing stadiums and their surroundings haven’t been built with sustainability in mind.

“The club was bought in 2015 by Right to Dream, and what we are willing now was built 20 years ago [by Tom Vernon]. I think what we can do is we can design it [Favrholm Stadionkvarter] according to our DNA, and this is difficult when what you have is preset.

“We will have different pathways for bicycles to make sure that it’s easy to access the stadium without coming by car – from a train, bus and bicycle point of view. Denmark is a big cycling nation and there’s a number of clever ways you can actually work them into the parking unit, because you can double park them, and, if you do it the right way, you can put them on top of each other.”

Kristensen makes it abundantly clear that extensive thought has not just gone into optimising each element of the development, but intertwining them: “We are more and more isolated with each other,” he says, “and the stadium itself is only more or less activated once every second week, but how do we make sure that there’s activities there, day in, day out throughout the year? When you want to be together with people you can come into the living room, and when you want to be by yourself, you can go to your own room or your own house.”

Kristensen says that “everything in the area is focusing on how to create win-win situations from an environmental point of view.” The region of North Zealand is known for its forests, but Hillerød has expanded out of what was once a glade. Favrholm Stadionkvarter will help restore the forests to become more cohesive with the rest of the region.

The social aspect of intertwining the development’s elements has evolved around what Kristensen calls ‘clever square metres’. This includes encouraging the hotel operator to use stadium conference rooms rather than building their own, using stored rainwater to water pitches instead of clean drinking water, and sharing parking spaces between the stadium and hospital.

“When they [school students] have domestic training, why are they not doing that in the hotel kitchen?” Kristensen argues. “With first aid, why are they not getting that training from either the hospital or from our doctors at the club?”

Plans that can enable such integrations are yet to be finalised, but the site has been designed to evolve over the long term. For example, if all the development’s residential units were marketed simultaneously, there wouldn’t be enough demand to maintain price. It is estimated that there will be around 10,000 more people working in Hillerød within the next 10 years than there are today. Novo Nordisk and Fujifilm, large pharmaceutical companies with facilities in Hillerød – the latter investing more than £1 billion in a new factory in the area – makes the town Northern Zealand’s hub. These companies generate enough excess heat to warm 20,000 homes on an annual basis, another consideration for Kristensen’s clever square metres.

Kristensen’s vision for Favrholm Stadionkvarter rests on the detailed version of the master plan being fully approved, which should be somewhat of a formality; all 27 members sitting on Hillerød city council voted in favour of the project.

Favrholm Stadionkvarter’s stability is enhanced by FC Nordsjælland not being the only stakeholder. An architectural competition launched for the project, leading to the master plan for the area being prepared by MASU Planning, Elkiær + Ebbeskov Arkitekter, PLH Arkitekter and OJ Rådgivende Ingeniører. A jury of 11 members selected this as the winning proposal, noted for its coherence linking the many facilities.

Their proposition even scrutinises glacial basins in Hillerød’s landscape that were formed during the Ice Age. Denmark is a mostly flat country, but soil movement caused by ice thousands of years ago in the area where Favrholm Stadionkvarter will be built means that from the site’s highest point to its lowest, there is about seven metres of difference to contend with. This won’t just require manipulating to produce a flat playing surface, but to build a four-metre-high soil wall to both protect pitches from the wind and absorb sound.

The Sports for Nature report, published by Loughborough University at the end of 2022, acknowledged that ‘loud noises are taken-for-granted aspects of the sport experience which can adversely impact the surrounding community and nature (Hammer, Swinburn, and Neitzel, 2014).’

“Football is considered as light industry,” Kristensen explains, “so if you put one of the pitches down here [near residences], you can only play on until six o’clock in the evening, then you need to close it down.” With the soil wall, activity on the pitches will be able to continue.

Such measures that enhance Favrholm Stadionkvarter’s environmental sustainability will be taught as part of Right to Dream’s curriculum. Tom Vernon prioritised education at Right to Dream’s inception, but Kristensen hopes the next stage of its evolution will include building a Right to Dream ‘Efterskole’, tailor made to those aiming to compete in sport at a high level.

An Efterskole is a voluntary school in Denmark, usually taken over a gap year and after 10th grade, before going to college. Around 100 children will be able to attend, both from Right to Dream’s FCN academy and players/staff from other sports teams hat don’t have the resources to provide their own Efterskole, such as Nordsjælland Håndbold.

“As a club and as a movement, we are very open to share; we want to share this with everybody that can get a benefit out of it,” Kristensen says, hinting at linking the Efterskole to the Egyptian and Ghanaian Right to Dream academies. “That international mindset where you buy into the values of the Right to Dream organisation – that is the school I want to build. This is what I’m most proud about.”

Kristensen has the right to be proud. Right to Dream continues reaping the rewards of what Vernon sowed: “When, for instance, the coaches say, ‘come over to me’, they’re there straightaway. They never talk to each other while you’re there,” Kristensen describes. “They listen to what you have to say. They put up their hand when they have a question. It’s just basic manners when I see them lacking in so many parts of society nowadays. A lot of our kids are getting socially handicapped in many aspects. This is why I’m at the FC Nordsjælland Right to Dream organisation.”

Even if Right to Dream academy products don’t make it to the first team, the value of what they carry with them isn’t overlooked: “I spoke to parents who had one of the kids in the academy some years ago,” Kristensen says, “and he didn’t qualify for the Superliga squad. He would have loved that, but how many things he’s got with him in his backpack from coming through this whole development and still having great friends from his time in the academy, and so many things he’d have learned.

“Not all of them can be playing down on the pitch, but we will have seven pitches now [at Favrholm Stadionkvarter]. Imagine the volume of people who can get through that. Not only when it comes to our own academy players, but for training sessions of outside players. We’ll have the resources and facilities to support it.”

Opt into our weekly newsletter for exclusive content focused on sustainability strategy, communication and leadership for sport’s ecosystem.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *