Unfettered capitalism has, in general terms, had a negative impact on fan influence, competition, and the environment. But what’s the alternative?

Can stakeholder capitalism work in sport?

That was the question posed by a group of promising international students (referred to as ‘Global Talents’) at the Impulse Summit 2021 in late-October. More specifically, can the stakeholder capitalism model create “long-term value” in the sports industry?

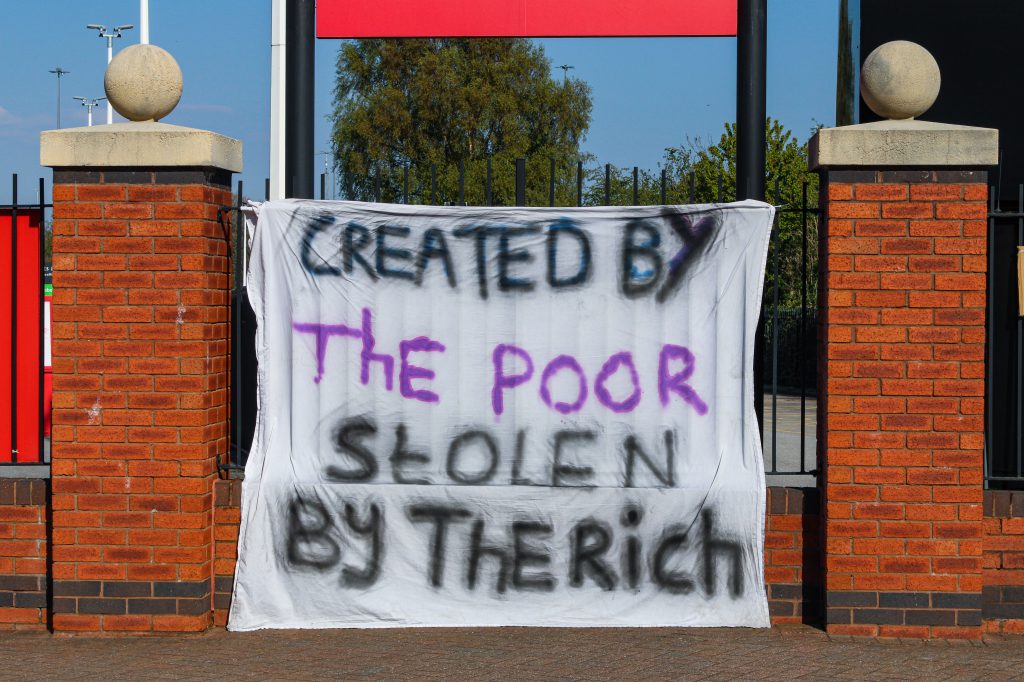

It’s a concept that has come to the fore fairly recently in sport, particularly following the botched attempt by 12 major football teams in England, Spain and Italy to break away from the status quo and establish a closed European Super League competition.

In what will go down as a milestone moment in European football history, fans of the 12 clubs revolted en masse, forcing a high-profile and embarrassing u-turn by most, with subsequent apologies and promises to give fans a greater say in the future decisions of those clubs.

The European Super League plan was a perfect demonstration of shareholder (or owner) priorities being totally at odds with almost every other stakeholder. It showed to some extent the hard-nosed, capitalist tendencies that dominate the thinking at the top of sport and the disregard of anything beyond earning more money.

But it also demonstrated that a powerful group of stakeholders working together to oppose something, in this case the fans, can scupper plans. During the Summit, Tom Pitts of LionRock Capital, part-owner of European Super League co-founder Inter Milan, admitted that he was surprised by the strength of feeling.

Critics of unfettered capitalism, which is the political and economic orthodoxy in much of the developed world, can justifiably point to data revealing that the gap between rich and poor has increased over the past few decades, causing or exacerbating numerous social problems.

The pursuit of economic growth has also had a disastrous impact on the environment. More than half of all the carbon emitted since the Industrial Revolution has been generated in the last 30 years. The loss of biodiversity has been on a similar trajectory in that same timeframe.

Top-level sport is often a microcosm of society, and those same critics of capitalism could also suggest that sport’s model is broken in its current form.

The majority of NFL franchises have seen their value mushroom over the last decade with very little relation to performance or competence. Aside from the 2017 season, the Jacksonville Jaguars have had a terrible recent run on the field, coming fourth out of four in the AFC South Conference every year since 2017.

During the 2020 season, they lost 15 out of 16 games, but according to Forbes’ ‘World’s Most Valuable Sports Teams 2021’, owner Shahid Khan has seen his $770m investment in 2011 surge to $2.45bn, with a 66% increase in value over the last five years alone.

In their 2019 paper exploring sport’s business models, and trying to find a ‘stakeholder optimisation approach’, Thomas Pittz, Joshua S. Benedickson, Birton J. Cowden and Phillip E. Davis acknowledged that the US-based business model for sports has “proliferated a system where a sole stakeholder group, the owners, accrues the majority of the value”.

And as more external investors buy stakes in (or outright takeover) European football clubs, a similar pattern is taking shape. The concentration of wealth at a handful of clubs is where the impact is potentially felt most keenly, where the best players go to a small pool of teams (as opposed to the US draft system) reducing competition.

Between 2001 and 2021, only teams from Spain, Italy, Germany, England and Portugal won the UEFA Champions League, with six clubs (Real Madrid, Chelsea, Liverpool, AC Milan, FC Bayern and FC Barcelona) collecting 17 of the 20 trophies at stake – Porto, in 2004 under the guidance of a young and dynamic Jose Mourinho, was very much an outlier.

In the preceding 20 years, teams from the above nations, plus Romania, the Netherlands, France and Serbia (then the Former Yugoslavia) picked up Europe’s top prize, with only Juventus and AC Milan of Italy, and Real Madrid of Spain winning it multiple times in that period.

Going back to the US, many ownership groups will put forward the argument that while their properties have increased in value – particularly those that have grown through the building of new facilities, in part, with taxpayers’ money – the team and the venue provides positive social and economic impact to the local community through jobs and spending.

However, that claim has been disputed and challenged multiple times by academic research and journalistic investigations.

So if the current system is only positively impacting a small group of individuals, and negatively impacting local communities (though accepting taxpayers’ money with questionable return), competition, and the environment, isn’t it time for a rethink? And, if so, is stakeholder capitalism the answer?

First, it is worth defining what stakeholder capitalism actually is.

According to McKinsey, the “principle” of stakeholder capitalism “requires business leaders to define their mission as creating long-term value not only for shareholders but also for customers, suppliers, employees, communities, and others.”

Far from going against the principle aim of capitalism – generating as much money for shareholders as possible – the consulting giant stresses that organisations with a long-term view (a stakeholder capitalism “essential”) outperformed other companies in terms of revenue, earnings, investment and job growth over a significant period of time.

McKinsey sets out five steps to making stakeholder capitalism work.

The first is to understand who the stakeholders are. In a typical corporate setting, internal stakeholders are employees, executives, the board, and shareholders. External stakeholders are customers and suppliers, governments, communities and the environment.

In sport, Pittz and his fellow researchers break down stakeholders into “primary and secondary” stakeholders: primary stakeholders include the league in which the team operates, the ownership group and the players – termed as “essential for its survival”. Secondary stakeholders include the local community, the local economy, and fans of the team.

However, you could make the argument that the primary stakeholders group defined in this instance is a little narrow. Fans of the 12 European Super League clubs gave a brief insight into the potential grave circumstances of mass boycotts by fans, for example.

With the acceleration of climate change and the extreme weather events disrupting sporting calendars, it’s fair to say that the environment – despite not being able to speak for itself – is a stakeholder that could justifiably be referred to as “essential for sport’s survival”. That’s why, to coincide with the COP26 climate summit, almost 50 sporting organisations, including the International Olympic Committee, Formula E, and Paris 2024, have committed to reducing their carbon emissions 50% by 2030 in order to achieve net zero by 2040.

FIFA, also on that list of signatories, has stressed the importance of protecting the natural environment and, as a consequence the health and wellbeing of fans and players. But if it decides to pursue a World Cup every two years instead of four, could that be perceived as putting profit ahead of people and planet, with all the likely extra air miles and carbon emissions that format would bring?

The next steps are to understand stakeholders’ needs and “build trust” (easier said than done, particularly in the US market where teams are snatched from communities and dropped into new cities with favourable tax laws), define and measure ways to serve stakeholders (including non-human stakeholders, like the environment), define and execute a stakeholder-capitalism strategy, and build an operating model that “can sustain long-term value creation for all stakeholders”.

This might seem like a huge departure for most sports teams and franchises, but the final four steps can be rolled into one strategic move articulated by Pittz’s study: shape ownership structures to optimise value for all stakeholders.

Acknowledging that the dominant US model of ownership – that provides owners with “all the economic benefits with negligible risks” – is not fit for purpose for the majority of stakeholders, Pittz puts forward the argument that a “maximised value partnership” in which the team is publicly-owned, not-for-profit, but still holding the ability to raise capital through the offering of a set number of shares to fans, could be the best way to maintain elite sporting performance, financial stability, and genuine stakeholder input.

In other words, the most likely way to achieve stakeholder capitalism in sport.

In the US, only the Green Bay Packers in the NFL have managed to make it work. The Packers have the biggest win percentage of any team in NFL history, and have managed to remain financially viable even though it occupies the NFL’s smallest market. Most notably, the team is owned by the local taxpayers and, as such, serves the local community first in many instances.

With that model of ownership now outlawed in the league (with the exception of the Packers), and the move away from fan-owned football clubs in Europe towards corporate ownership groups and rich benefactors, implementing stakeholder capitalism in elite sport has to be more nuanced than wholesale revolution.

In 2020, World Economic Forum published a report demonstrating how organisations could measure stakeholder capitalism, with principles in the realm of governance, planet, people and prosperity.

Planet core metrics include the measurement of greenhouse gas emissions and land-use sensitivity, while core people metrics feature diversity and inclusion, training provided, and health and safety – all issues relevant to elite sports properties.

Whether it’s through the overhaul of ownership structures or a more evolutionary approach like the adoption of certain stakeholder metrics, organisations at the pinnacle of sport will have to make a change one way or another if true stakeholder capitalism can thrive.

Opt into our weekly newsletter for exclusive content focused on sustainability strategy, communication and leadership for sport’s ecosystem.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *