Social Return on Investment model developed UEFA, the European football body, aims to demonstrate that an investment in grassroots football can generate positive societal impacts

It’s often said that football is more than a sport – it’s the world’s game. An estimated four billion people – half of the world’s population – would consider themselves fans of football, while 270 million people play the sport globally.

All of that engagement inevitably leads to economic and social impact, well beyond the professional game. Grassroots football can help stimulate inclusion and integration. It can lead to improved health and wellbeing for those playing. But up until now, putting reliable figures on these positive social and economic impacts has proven complex.

Recognising this, UEFA – the sport’s governing body in Europe – sought to find a model to measure football’s added value. Working with several top academics and practitioners in the field, a UEFA programme called Grow developed a Social Return on Investment model that quantifies both the positive social consequences of football and its overall economic impact.

UEFA set up Grow to provide a range of strategic development services to Europe’s 55 national associations. It is hoped that the SROI model will help individual associations make an evidence-based case for increased government investment in amateur football.

Since 2017, the SROI model has so far been applied to 25 national associations. It calculates that the total 8.6 million registered footballers in these countries generate a cumulative €39.5bn in positive economic, social and health impacts.

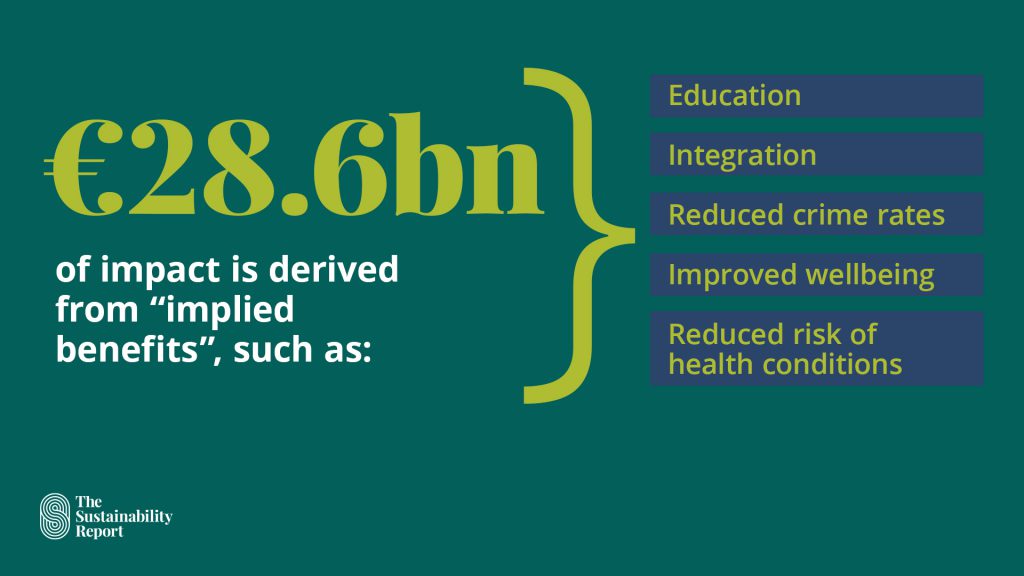

A proportion of this figure (€10.8bn) comes directly through membership fees, job creation and investment in facilities. However, the lion’s share (€28.6bn) is derived from “implied benefits” relating to education, integration, reduced crime rates, improved wellbeing, and reduced risk of type II diabetes and heart disease.

UEFA describes the SROI as a “form of cost benefit analysis that attempts to quantify and place monetary value on social change”, and was developed to “build a coherent business case” to attract government investment.

“Historically, football has offered many opportunities for youth and adult men to be physically active,” Zoran Lakovic, National Associations director, tells The Sustainability Report. “More recently, there is a focus on inclusivity which is really positive. Positive for the individuals, communities and society at large.”

In Poland, which traditionally emphasised the development of the men’s elite game, the SROI model has seen a renewed focus on football being used as a force for inclusion and preventative health measures. After presenting its government with its preliminary SROI research figures, Poland’s National Football Association (FA) successfully secured €45m in grant funding over a three-year period to invest in creating more opportunities for people to play football.

The government, says Magda Urbańska, the director of grassroots at the Polish FA, was motivated by the data concerning the health benefits linked to playing regular football, and was convinced that the sport could play a preventative role for a handful of serious illnesses.

Heart disease, for instance, is the major cause of death in Poland and is a condition that regular, moderate exercise, such as football, can help reduce. Urbańska explains that improving people’s mental health during arduous COVID-19 lockdowns also helped reinforce the FA’s case.

“For us, there are three main benefits,” she adds. “The first is that it helps us address issues locally, as well as nationally. The second is about image. We, as the Polish FA, can now talk on a totally different level with the government. They no longer see us asking for grants, but asking for investment. And the third main benefit is that we have also secured more private sponsorship revenue thanks to this model.”

In essence, the model is designed to show governments that an investment in football will help them save money in other areas. Aside from the physical healthcare aspect, the SROI model is able to put a monetary value on football’s positive effect on subjective wellbeing.

According to Dr Tim Crabbe, chief executive of Substance (the research and technology company that curated the research and experience of advisory board members to develop the SROI model), the value of football’s impact on subjective wellbeing was discovered through academic research that considers people’s ‘willingness to pay’ to play the game.

“We’re able to draw on a range of different approaches that come from established, high-quality peer-reviewed research,” Crabbe explains. “We know that people playing football regularly can reduce a whole range of health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and some cancers. There’s evidence of impact on mental health, in terms of anxiety, depression, schizophrenia.

“But the research also shows social benefits, such as a reduced likelihood of people getting involved in the criminal justice system and in terms of people’s greater propensity to be employed. Involvement in regular organised football can lead to improved educational performance and, potentially, to greater lifetime earnings.”

The SROI model leverages learnings from a formula developed by Crabbe in 2013 to explore the economic impact derived from positive social impacts of playing sport. The formula identifies the likelihood of different types of people turning to crime, dropping out of education, abusing substances, and becoming obese, against the percentage of how much that risk is reduced through the playing of regular sport. Where we know the monetary cost of the negative outcome, the monetary cost savings of that individual avoiding the negative outcome (i.e. doesn’t turn to crime, become obese, or fall out of education) can be calculated.

For example, if there’s a 52.5% risk of an individual turning to crime and playing sport reduces that risk by 15.81%, the average cost saving would equal €817 per individual if the cost of the negative outcome is €5,176. Applying that calculation across a large number of people can represent significant cost savings for local and national governments.

In three pilot projects, UEFA helped the German, Estonian and Albanian football associations apply the SROI model to show the economic benefits of football within each nation. The headline figures relate to overall economic impact of participation – €13.9bn, €79.1m, and €45.2m respectively – but a deeper look uncovers some interesting outcomes.

In Germany, for example, €4.9bn of the €5.6bn of the health savings generated by playing football came from subjective wellbeing, indicating quite strongly the positive mental health consequences of participation. To paint a full picture, UEFA’s SROI model showcases some of the negative economic impacts that football is responsible for as well, such as injury. In Germany, for instance, €44.4m was removed from the national balance sheet because of injuries obtained by people playing football.

“Increasingly, the academic panel is looking to model the ways in which football has a negative impact, beyond injuries, so that we can provide as much balance to the story as possible,” says Crabbe. “But we’re doing this with a view to reducing those negative impacts.”

Such negative impacts could be related to the environment (carbon emissions generated by those travelling to play football) or society (tribalism and racism facilitated by football participation).

During this second iteration of the SROI model, UEFA worked alongside the Scottish FA to test the principles on clubs at a more micro level. Two clubs – Ayr United Football Academy and Spartans Community Football Academy – are taking part, with Danny Bisland, national club manager at the Scottish FA, overseeing the project.

“These are community anchor organisations, and in my 20 years working for the association I’ve seen that football has a reach beyond anything else,” Bisland says. “Beyond any statutory organisation, any social organisation – football has a reach that’s incredible. It talks to parts of society that wouldn’t normally engage.”

The Scottish FA’s first SROI project, conducted in 2018 on a more national basis, demonstrated that participation among officially registered grassroots players generated €565m. When the model was extended to include all football players, this figure rose to €1bn.

Such large numbers failed to provide real context and detail. To address this and illustrate how football positively contributes to communities, the model was applied to Ayr United Football Academy and Spartans Community Football Academy, based in the capital Edinburgh. Located on the west coast of Scotland, Ayr has a high rate of child poverty, while Spartans Community Football Academy lies in an inner-city area of northern Edinburgh – two scenarios that reflect circumstances and challenges facing many other clubs across Europe.

According to the SROI modelling, Ayr United Football Academy generates €10m in local community benefits through subjective wellbeing (€4.8m), mental health (€500,000), tackling dementia (€275,000), combatting absences from school (€250,000), and educational attainment (€350,000). Spartans contributed a total of €6m to its community, with the majority benefitting infrastructure investment (€2.5m), volunteering (€1m), and subjective wellbeing (€1.5m).

As the SROI model is progressively applied to other community clubs, Bisland – like Urbańska – is encouraged that the verified economic outcomes are supporting the Scottish FA’s high-level conversations with government officials.

“The Scottish government framework is focused on societal outcomes as well as economic. It’s about a healthier, happier society,” he says. “We can talk about really significant figures and how they relate to national performance framework outcomes, and also the UN Sustainable Development Goals. It’s a really powerful narrative.”

The SROI model will continue to be refined to reflect new research around volunteering and subjective wellbeing. Alongside Substance, UEFA is additionally looking to develop a materiality index that accurately demonstrates the positive and negative societal and economic impacts of amateur football

Crabbe adds: “We will continue moving this down to club level. As individual clubs use the model, they will enter data and reveal a story. If we have thousands of clubs capturing data around what their football club is providing in terms of this type of impact, we can start to learn where the greatest impact is happening and the project itself becomes more self-sustaining. That would be the hope.”

Get more exclusive content like this by signing up to our newsletter here.

3 Comments

Sikhumbuzo Ndebele

February 11, 2021, 6:49 ama good read

REPLYSteven

February 14, 2021, 4:48 pmVery Informative.

REPLYAngelo Martins

October 25, 2023, 4:56 pmHi Matthew. I have found the reading extremely positive and interesting. I would love to receive more information on this subject.

Congratulations on your article

REPLY