Evidence is building that emphatically demonstrates how teams, leagues and federations are being impacted by extreme weather – but can sports organisations take steps to reduce their vulnerability to the elements?

Vulnerable. If you could choose one word to describe how the world is currently feeling, ‘vulnerable’ would be a strong contender.

The Covid-19 pandemic has made people feel vulnerable about their health and employment status. Others, who oppose lockdown, feel a certain vulnerability regarding their freedom. And then there are businesses and whole sectors that are losing unimaginable amounts of money as the world around them gets to grips with the crisis.

Sport is among those industries and its vulnerability to global issues of this type has been laid bare.

Sporting events thought to be untouchable, like the Olympic Games, UEFA European Championships, and top level soccer, American football, basketball and baseball, have been wiped off the calendar as quickly as you can flick off a light switch, with no certainty about when they will return.

Financially, it has been a disaster. An ESPN study discovered that at least $12bn will be wiped from sport’s collective balance sheet, while sports marketing company Two Circles has estimated that sport sponsorship could plummet by more than $17bn year-on-year (37%).

But what if Covid-19 is just the tip of the iceberg? While it currently dominates societal discourse, many experts remain steadfast in their view that climate change will cause far more disruption and claim many more lives than the virus.

The question for sport is clear: if climate change progresses at the rate that’s expected, will competitions and leagues be impacted in a similar way to the pandemic? And if so, what can sports organisations do to mitigate that risk so a similar shutdown needn’t occur.

A myriad of concerns

The first thing to remember is that the two problems – Covid-19 and climate change – are not the same, but related. Indeed, the World Health Organization expects the changing environment to accelerate the spread of other infectious diseases. So as the world heats up, the chances of another Covid-19-like pandemic occurring becomes much more likely.

Sport, however, has a myriad of concerns when it comes to climate change. The wider, global consequence of climate change is clear: if we continue on the current trajectory we won’t be able to limit global warming to 1.5°c above pre-industrial levels and, according to the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), that will trigger irreversible and catastrophic changes within the next decade.

What this means for sport has been documented in a number of recently-published research reports, and is likely to remain a key part of sporting academia as the state of play worsens.

The Climate Coalition, a UK-based movement of more than 140 members, published perhaps the most well-documented piece of research in this field in early 2018. The ‘Game Changer’ report, published in association with the Priestly International Centre for Climate, looked at the impact climate change was having on sports key to British culture, such as football (soccer), cricket and golf, as well as winter sports. The findings made for concerning reading.

Firstly, the context: the report reveals that the UK, as a nation, is becoming wetter and warmer. As a consequence, the last 30 years has brought an “increase in extreme weather events”, like heavy rainfall, flooding and storms.

Winter rainfall is estimated to increase by 70-100% by 2080, but in the summer rainfall will decrease by 40% over the same period – meaning that extremely wet winters and summers beset by drought will likely be the norm going forward.

The result is potentially disastrous for football, the UK’s national sport, which is played by around 2.3 million people. Extreme weather is already having a major impact on the grassroots game. According to the Game Changer report, a third of amateur clubs are losing around two or three months of the playing season because of bad weather.

In the professional game, at lower league level, the 2015/16 season saw the cancellation of 25 matches. Carlisle United, playing in the third tier of English football, was forced out of its Brunton Park home for 49 days because of Storm Desmond – an incident that cost the club £200,000.

For clubs outside the English Premier League reliant on match day revenue, extended periods of disruption would be a threat to their very survival. Indeed, the halt in the season caused by the coronavirus pandemic has put many football clubs on the brink of going out of business.

There are similar threats being posed to both golf and cricket. The former is facing a number of big problems related to extreme weather. Most concerningly for the one-in-six courses located on Scotland’s coastline, the rising sea levels and coastal erosion could see them disappear from the landscape completely.

“Climate change is certainly becoming a factor,” Steve Isaac, The R&A’s director of sustainability, told the Climate Coalition. “Golf is impacted by climate change more than most other sports. Trends associated with climate change are resulting in periods of course closures, even during summer, with disruption seen to some professional tournaments.”

Disruptions can be seen throughout the course of the year; wetter autumns and winters result in muddy conditions and more turf diseases, while in the summer drier conditions negatively affect the quality of surfaces.

Impaired performance

But despite the challenges facing football and golf, the report acknowledges that, of all the pitch sports, cricket will be the hardest hit by climate change – no matter if it is being played in England, Australia or Bangladesh.

A few statistics from the report: since 2000, 27% of England’s One Day International matches have been shortened because of rain disruptions, while the rate of rain-affected matches has more than doubled since 2011.

The ‘Hit for Six’ report, created by the Priestly International Centre for Climate, the British Association for Sustainable Sport (BASIS) and the University of Portsmouth, extended the study on cricket and broke the climate impact on the sport down into three main risks: heat, drought, and extreme storms.

Extreme heat is a major issue for those playing the game, particularly batsmen and wicketkeepers who wear heavy padding and helmets to protect themselves from the ball. As heat rises, players can go through nine stages of discomfort, increasing in severity each step: fatigue, profuse sweating, thirst, weakness, faintness or dizziness, sensation of sweating, heatstroke and nausea, and medical emergency.

Looking at it from a purely sporting point of view (before you even take into account the duty of care to the players’ health), these nine stages will inevitably lead to an impaired performance.

In fact, athlete health and level of performance is among the most tangible vulnerabilities sport has in relation to climate change.

In her piece of work investigating the potential impacts of climate change on baseball and cross-country skiing, Dr. Madeleine Orr found that baseball players competing during a time of increased heat and moisture could be putting themselves in significant danger of succumbing to heat exhaustion and heat stress.

For cross-country skiers, the shortening winter season and the increase in low-snow years dramatically reduces the opportunities for elite athletes and recreational skiers to hone their craft, train and compete in tournaments.

For both sports, this is only going to get worse as time goes on. Just looking at one location in which both sports are popular, Eastern North America, the climatic changes that will seriously impact baseball and cross-country skiing will accelerate over the next 50 or so years.

By 2065, summers will be 1.3°c hotter, there will be a 3% increase in summer precipitation, coastal flooding will become more prevalent, winter temperatures will surge by 1.4°c, winter precipitation will increase by 5%, and snow melt will get faster.

The ‘problem state’

The research paints a pretty stark picture that there’s no getting away from: sport is already being substantially impacted by climate change, and this is only going to get worse.

While a handful of forward-thinking sports organisations are taking climate action through emissions reduction and related sustainability programmes, the fact is that the sports industry in isolation won’t be able to halt or slow climate change alone.

That being said, there are a number of policies and strategies that entities in the sports sector can adopt to make sure that this changing climate will have a minimum negative impact on their sport and organisation.

According to Orr, there are two major aspects to climate change risk that sports organisations should be most aware of: the business side of things, in which money is lost due to games being called off, and the opportunity loss, particularly for athletes competing and training.

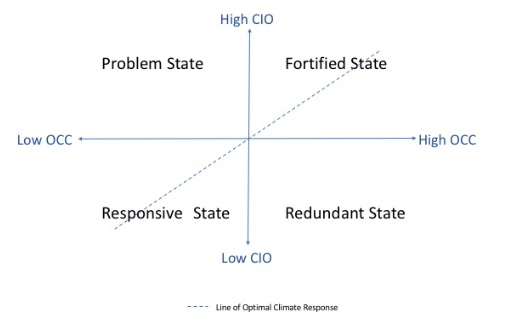

To help sports organisations figure out where they are in terms of their own vulnerability and potential to mitigate climate risks, Orr devised the Climate Vulnerability of Sport Organizations Framework, or CVSO. Developed alongside Dr. Yuhei Inoue, the CVSO (below) is broken down into four quadrants: the responsive state, the problem state, the fortified state and the redundant state.

The responsive state refers to sporting organisations that are experiencing, or are likely to experience, minimal negative impact from climate change and, as a result, have a low capacity to respond. The fortified state refers to teams, leagues or federations that are experiencing significant climate impacts, but have got policy, procedure and resources in place to mitigate that threat. Those in the redundant state have all the policies and resources in place, but not a huge amount of climate risk.

And then there’s the problem state – a situation in which a sports organisation is facing significant climate risks but doesn’t have the adequate policies, procedures and resources to counter it. It’s a position that many sports organisations find themselves in (particularly amateur clubs), says Orr.

Essentially, the quadrant your sports organisation finds itself depends totally on the climate risks it faces against its ability to deal with those issues. In other words, it all comes down to ‘preparedness’.

Orr’s work reveals that there are four ways to determine how vulnerable your sport or organisation is to climate change: your organisation’s location, its season of play, the types of hazards it faces, and the type of sport it plays.

It may seem that, on the face of it, there’s not a huge amount sports organisations can do about any of the above issues. Teams rarely change their geography, leagues seldom alter their season of play, types of hazards are uncontrollable, and changing the sport it plays means totally reinventing itself as an organisation, which is unfeasible.

But within her research, Orr has outlined a set of factors that organisations can use to mitigate the negative effects of climate change regardless.

The first is economic and revolves around the designation of contingency budgets and purchasing adequate insurance policies related to climate risk in order to safeguard the organisation in case an extreme weather event has a severe impact on the playing schedule or sports facility.

At the top end of the scale – and slightly unrelated to climate issues – Orr highlights Wimbledon’s foresight for investing in pandemic insurance (to the tune of $1.9m per year), which is estimated to pay out $142m in light of the current Covid-19 outbreak.

Other recommendations include staff training around climate science and hazards, the creation of risk management strategies, tapping in to network resources (such as liaising with other clubs, consultants and academics), making infrastructure more resilient, and relying on natural resources (such as planting native plants that take in water at the correct rate and reduce scope for flooding).

Mitigation policies

Not all sports organisations are totally unprepared for climate change. For some, it has become a key part of their planning, particularly when it comes to hosting important events.

In Australia, where extreme heat has become a growing issue for most sports, forward-thinking organisations have implemented policies to reduce or mitigate the associated risks.

Grand Slam tennis tournament, the Australian Open, has attracted the world’s attention for its battle against the elements as much as it has for the world-class tennis on display. It’s an important event, contributing 2-3% of the nation’s GDP. But the tournament has seen several major disruptions over the years as a result of the changing climate.

This was most starkly felt during the 2020 event, when smoke from bushfires surrounding Melbourne appeared to have a negative effect on the players, with world number 210 Dalila Jakupovic pulling out because of the poor air quality.

Heat, generally, has been the biggest cause for concern during recent tournaments. According to the Australian Conservation Foundation, court surface temperatures hit an astonishing 69°c in 2018 as Alize Cornet collapsed on court. In 2014, nine players withdrew and more than 1,000 spectators had to be treated for heat illnesses.

Understanding the scale of the problem, Tennis Australia established a Heat Stress Scale in 2018 to replace its existing Extreme Heat Policy. The scale measures air temperature, as well as humidity, reflected heat and wind condition to provide a rating between 1-5.

When the scale reads 4, then players are permitted to take extra heat breaks. Match officials are permitted to suspend play when there’s a reading of 5.

However, while Tennis Australia has that policy in place, the likelihood is that temperatures will continue to rise during January in Australia. To be in the fortified state of the CSVO, the organiser may have to implement further contingencies, like moving the Australian Open to a more accommodating part of the year, for example.

Golf, as described earlier, is facing a multitude of threats related to climate change, but some progressive course operators are adapting to new, more challenging conditions. In Northern Italy, which is located in golf’s transition zone (a bridge between the colder and warmer areas where golf is played), many courses are moving from turf that used to work better during cool season to warm season grass as the rising temperatures make that the better option.

As well as being better prepared for droughts and periods of hot weather, warm-season grasses are more “disease tolerant” and offer “better year-round playing quality at lower costs”, says Jonathan Smith, the executive director of the GEO (Golf Environment Organisation) Foundation.

But, for Smith, safeguarding vulnerable courses from the impact of climate change is about more than just alternating turf.

“There will be parts of the world where the water dependency might require a more holistic look, not just change turf grasses to reduce water use by 30%, but going beyond that,” he tells The Sustainability Report. “We’re big advocates of golf clubs reimagining their landscapes, stepping back and thinking about drought, disease, water shortages and flooding.”

He adds: “We try to look at what would be an integrated response to the risks of hot and dry and the risk of too wet. Then you start getting into an ecosystem view of the golf landscape – looking at water supply, naturalisation, traditional pipe drainage versus open water features. It’s about seeing water as an asset rather than a liability, thinking about where we can save it, and building up playing surfaces so they are more freely draining.”

Barriers

However, there are a few barriers the sports industry as a whole needs to overcome to move out of the problem state and into the fortified state.

The first, says Orr, is perceiving vulnerability as an opportunity instead of a weakness. She cites the work of Brené Brown, a celebrated academic who argues that acknowledging vulnerability is a strength not a weakness, as a potential source of inspiration. Within that vulnerability, she says, sports entities can find ways to improve their businesses, make the operation more efficient, upskill staff, and make the organisation stronger in the process.

Secondly, she suggests that within many organisations (not just sport), climate change is perceived as a policy issue, not a business issue, which holds people back from discussing it. A related concern is that, particularly in the US, climate change can be a polarising topic that many professionals would prefer to avoid out of fear of appearing too political.

In both cases, Orr explains that instead of trying to tackle climate change as a broad topic, a better approach is to address “one hazard at a time”, such as rain patterns on pitch quality and extreme heat on the health and performance of athletes – essentially, tying climate impacts to the bottom line and avoiding language perceived as partisan.

The lack of education around climate science and environmental resources among sports managers is also a fundamental problem – particularly as “people don’t want to talk about something they don’t know about.”

That’s where training and awareness among staff, and broadening network resources to researchers, external experts and fellow sports managers can help close the knowledge gap, Orr states.

“We are all vulnerable to climate change, but if we address it head on it can really produce some interesting outcomes and make our organisations more resilient,” she says. “And the lack of taking those actions actually makes us more vulnerable than we would have been had we done it.”

2 Comments

Paul Sinclair

May 21, 2020, 10:31 pmThanks for the article – its so great to see this leadership!

REPLYLuke Mulley

November 13, 2020, 1:57 pmHi Matthew, very interesting article and a great read.

I would like to draw attention to the cited 2-3% of Australian GDP generated by the Australian Open. It seems this figure originates from the Boston Consulting Group ‘Intergenerational Review of Australian Sport 2017’ which states:

"Sport makes a valuable contribution to the economy. Over $12 billion is spent annually on sport and sports infrastructure each year, which supports over $39 billion of economic activity across the country. This corresponds to the equivalent of 2-3% of Australia’s GDP."

Consequently, I think this is misleading/incorrect use of the 2-3% figure – it corresponds to all Australian sport, not just the Australian Open.

REPLY