Miami’s coral reef is facing existential threat due to climate change. During its regatta series, World Sailing – and its sailors – stepped up to bolster the local area’s underwater ecosystem

Melting ice caps and mass deforestation have become an all too recognisable sight when environmental damage is discussed in current affairs, with stark images from the Arctic Sea and the Amazon rainforest imprinted on the minds of viewers.

The destruction of the world’s coral reefs may garner less attention in comparison, but these enchanting parts of the ecosystem are much more important than many may realise. They protect coastlines from the sea and act as a habitat for diverse species of underwater creatures.

According to The Economist, more than 130 million people in the Coral Triangle alone (an area in Southeast Asia covering the waters of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Papua New Guinea) rely on reefs for their livelihood, be it for food, or income via tourism and fishing. The deterioration of reefs could spell economic disaster for these nations.

Inevitably, those involved in ocean-based water sports are also concerned about the health of marine life. They regularly see the effects of environmental damage first hand during competition or training.

World Sailing is one of the most prominent sporting bodies raising awareness of the damage being done to the oceans. Following the appointment of a Sustainability Commission two years ago, the federation has greatly increased its dedication to sustainability on all fronts and is trying to fight back against the damage caused with innovative yet practical measures.

Dan Reading, head of sustainability at World Sailing (below), leads the work programme devised by the Commission, and told The Sustainability Report about the extent of the problem.

“We’ve heard lots of compelling stories about people in the middle of the ocean where the closest person to them is someone on the International Space Station and they still come across pollution. There can be hardly any people around but the effects are still felt in the most remote parts of the world.”

Perfect opportunity

Sailing’s Hempel World Cup Series was identified by Reading and World Sailing as the perfect opportunity to expand the federation’s efforts. Beach cleans have been a regular feature, and include the participation of World Cup sailors in addition to local sailors and supporters.

In the 2020 Hempel World Cup Series Miami, the pre-competition mangrove clean collected around 250kg of plastic on just one small area next to the competition venue. Reading could see that this had an immediate effect on the younger volunteers who helped out.

“I heard one of the local kids say, ‘I work in a supermarket and I’ve found all these plastic bags. Now I’m going to try to make more people avoid non-reusable bags.’”

Clearly, the removal of a quarter of a ton of waste from the mangrove is a significant short-term victory, but fulfilling World Sailing’s larger goal of education and inspiration is far more meaningful. The hope is that through this raising of awareness, the message can spread.

In previous years, as part of these educational efforts, World Sailing had helped the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science through outreach programmes and donations involving their Rescue a Reef project. This project is focused on restoring and protecting coral reefs in the South Florida area, while also acting as a key research project with the overarching goal of improving the health of reefs globally.

For the 2020 World Cup Series, Reading decided that more could be done to promote this programme and spread the message even further. Consequently, the two institutions decided to collaborate on the project: sailors and World Sailing staff would go on Rescue a Reef’s scuba dives and see the scientific operation first hand.

Initially set up by Dr Diego Lirman, Dalton Hesley is now the project manager of Rescue a Reef, which he oversees alongside his work as a senior research associate at the Rosenstiel School.

“Our coral reefs can absorb up to 97% of offshore wave energy, which is regular everyday wear and tear that would otherwise cause coastal erosion,” Helsey explains. “And when you consider hurricanes and storms, having that line of defence is so critical.

“Millions of people travel to Miami every year for our beaches, our offshore boating recreation, fishing, scuba diving, so if we see this ecological damage, we’re going to lose those economic drivers; it provides jobs, food. As we lose reef resources, we’re going to see fish communities decline as well. But reefs are also connected to the air we breathe. I believe it’s roughly one in every three breaths we take are thanks to healthy coral reefs and the services they provide. And it’s not just at a local level that we see these benefits or economic drivers: it’s worldwide.”

Coral bleaching

Around the world, coral reefs are under threat in numerous ways. An increase in the average sea temperature can lead to “coral bleaching” – a process where the coral turns white and becomes more stressed and subject to mortality; aggressive fishing practices can also lead to the destruction of corals, as nets become entangled with the reef; and increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can make it difficult for corals to grow and reproduce.

As such, projects like Rescue a Reef are protecting the planet via the coral reefs and the resulting research. The project has allowed Hesley and his team to expand their coral nursery in the local area by the university and focus on restoration and maintenance of nearby corals. A coral nursery is an artificial coral farm where coral is encouraged to grow in a protected area, often on underwater ‘trees’.

The field work of the project can be broken down into two steps. Firstly, a team of scuba divers visits the underwater nursery in order to cut small pieces of coral from a larger colony of coral. These fragments are then brought up to the boat, stored in seawater coolers and transferred back to the local reef restoration site.

The reef restoration site is usually a local reef which has been identified as ‘at risk’ by Hesley and the team, and this is where the second part of the process takes place. These reefs have been classified as ‘at risk’ owing to low coral cover, low fish abundance and general need of restoration.

Here, the fragments of coral which have been collected are attached to the reef floor. This can be done in a number of different ways such as using cable ties, a hammer and nail, or even just wedging corals between crevices, but Rescue a Reef opts for an underwater cement that fixes the coral to the reef floor.

Hesley explained why growing the reefs in this manner is so effective.

“This works really well because corals respond very positively to fragmenting. Not only will the lesion heal, but the coral will actually grow faster than it was previously, and that’s how we’ve been able to scale up.

“We can start with 100 pieces, grow them, cut them into 200 pieces, grow all 200, cut those into 400 pieces and so on. That’s what has made it sustainable and feasible for us to scale up.”

As this goes on, resulting growth then becomes eligible for fragmentation itself which allows the eventual creation of new colonies in the nursery in a process called propagation.

Tricky conditions

In an ideal week, Rescue a Reef spends two days working in the lab and three days in the field, dependent on the weather conditions.

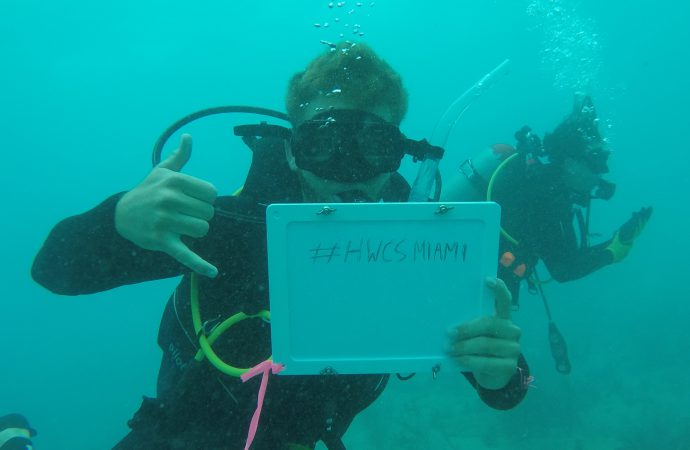

After an introductory training session, World Sailing staff and sailors were tasked with joining the practical work in the field, collecting coral samples from the nursery and then fixing them to the reef floor in the reef restoration centre.

Fortunately those who were involved in the work were comfortable on the water – conditions were tricky, but Hesley was thrilled with how well the work was carried out, as well as with the impact of World Sailing and the athletes spreading the word afterwards.

“World Sailing and the athletes shared it through their social platforms. For them to voice that message, I think it carries a lot more weight and impact than if we were to do it so we were very grateful to have them express their interest and support.

“We’re ecstatic when groups like World Sailing approach us and say, ‘we love what you’re doing, we not only want to team up with you, but we want to promote and advance your efforts even further.”

Reading also realised the importance of combining the technical expertise of Hesley and the Rescue a Reef team and the voice of the sailors.

“It was important to get some fantastic scientists who could explain what they were doing so well. They recognise that there are limitations because they can talk about science to everybody, but athletes have the following on social media, which can be great to engage people on these issues,” he says.

“One of the objectives was to make sure that some of these guys and girls can be better informed but also to use their power as athletes to engage people on these topics.”

Challenge 2024

As Rescue a Reef’s ultimate goal is large-scale change via governmental policies, World Sailing’s contribution in raising awareness and the scale of the project will ensure more people take notice.

In addition to the work around coral reefs, World Sailing is also pioneering some innovative new measures for use in competitions.

The federation identified that a large proportion of their carbon emissions were coming from fuel for support boats during competitions, normally via a petrol-powered machines. As a result, World Sailing set up Challenge 2024, an initiative to use research institutions to create boats which are either electric or hydrogen powered, in an effort to reduce emissions to zero.

“There was a boat that was launched [at the beginning of 2020] that was the first completely electric-powered coach boat and I think that’s in part because of our initiative,” said Reading.

“At the moment there’s not really any incentives for people to go electric, but we think that we could be that incentive by integrating it into our rules and that the market will start to create low-carbon boats. Then they can be bought by people who want to use them recreationally, the RNLI, coastguards etc.”

This, of course, creates the issue of affordability for the less well-off participants in World Sailing events, but the federation would ensure a level playing field, potentially by renting boats out to these nations rather than obliging ownership.

In the long term, though, the new boats have the potential to save money for owners.

“To charge one of these boats would cost around £8-9 in electricity so you can compare that to a full tank of fuel which might be around £40. If you’re using the boat every day, which professional teams tend to do, there is actually a relatively short payback,” said Reading.

All in all, World Sailing has taken its commitment to sustainability seriously with a broad range of 56 sustainability targets as part of its ‘Sustainability Agenda 2030’. In addition to these long term solutions of reducing fuel usage and educating local communities, other measures like stacking boats more efficiently for transport to events and competitors’ bibs being made of 80% ocean nylon (disused fishing nets) have been inspiring other sports.

“If the canoeists and rowers, for example, want to use the same materials [for bibs] then that’s great, we would only encourage that because it’s not a competition. We need to all work together towards the same goal,” Reading adds.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *