Athletics federation tests air quality in a road race for the first time – and prepares to conduct clinical research with athletes when the project’s pilot phase concludes

All eyes were on Vivian Kiplagat as she crossed the finish line of the 2019 Mexico City Marathon. In doing so, she broke the record for the women’s race by almost three minutes and became the first Kenyan woman to taste victory in the Mexican capital for eight years.

Her extraordinary win grabbed the headlines, and rightly so. But in the background something even more significant was happening that could impact all runners – from Kiplagat at the top of the tree, to the recreational jogger trying to stay in shape.

On Sunday, the Mexico City Marathon became the first certified marathon in the world to measure air quality along the entire route while the 25,000 participants were competing.

It was the next bold step in an ambitious air quality pilot project being conducted by the IAAF as it attempts to find out how air pollution impacts athlete performance and health and, in the long-run, discover the best times and locations to host its events to mitigate negative consequences.

Before Mexico City, the majority of the pilot project had been conducted in stadiums. Technology partner Kunak has been integrating air quality monitors in a number of stadiums around the world since last autumn, in Monaco, Addis Ababa, Sydney and Yokohama.

But with dozens of IAAF certified road races occurring every year – in major cities that, generally, are susceptible to large amounts of air pollution – the governing body decided to start gathering data.

“From a scientific perspective, road races and urban settings are great,” says Paolo Emilio Adami, IAAF’s sports medicine specialist. “That’s because of the time and exposure of athletes when they’re competing, which is between two to six hours, and of the different environmental factors that come into play when we talk about an urban setting.”

Adami adds: “Each and every city is different. Climatic changes, seasons of the year – we need to understand what happens and adapt to each and every location based on its needs, number of participants and characteristics of the race.”

“The idea is, in time, to be able to offer advice to those who develop course routes,” says Jackie Brock-Doyle, who is overseeing the strategic element of the IAAF’s air quality project. “Maybe creating a loop course might not be the best thing to do – maybe it’s better to go from A to B. Perhaps it might be better to change the transport system a week before a marathon compared to the day before.”

The Mexican government, says Brock-Doyle, have been “really brilliant partners” who “genuinely want to make a change”. Indeed, Mexico City will provide IAAF data from its own air quality devices to compare with the results garnered by Kunak’s machines – including one device that was strapped to a bicycle and taken through the length of the course.

Major challenges

A city of almost nine million inhabitants, Mexico City has major challenges regarding the quality of its air. It’s had an air quality improvement programme in force since the 1990’s, which has brought the level of primary pollutants – such as nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and volatile organic compounds – down by 90%.

However, the city still has issues regarding the reduction of secondary pollutants, such as ozone and PM2.5 (atmospheric particulate matter). According to Sergio Zirath Hernández Villaseñor, the general director of air quality for Mexico City, the problem is exacerbated by meteorological conditions, including its atmospheric chemistry, altitude and surrounding mountains.

“We would like to know if air quality monitoring during races, such as the marathon, is useful in designing recommendations for athletes, the IAAF and the city itself to reduce exposure,” Hernández Villaseñor tells The Sustainability Report.

“Going beyond the objectives of the specific marathon project, data collected in the days before, during and after the race could be used to assess people’s exposure during typical days when traffic is normal and on one extraordinary day when traffic in the city is restricted. This could help design and justify policies to improve air quality and reduce people’s exposure, such as a low emission zone in the centre of Mexico City, where lots of people congregate.”

Javi Carvallo Chinchilla, the director of the Mexico City Marathon, concurs.

“There may be a risk that people will not think it’s safe to run in Mexico City, but on the other hand I don’t want to risk the health of any person – that’s the most important thing,” he says. “I’m very excited about seeing the results and to speak with the Mexican government about how air pollution might or might not affect not only runners, but people who live in the city. Depending on the results, there might be some changes in policy.”

Yokohama study

Brock-Doyle and Adami are both enthusiastic about the prospect of the IAAF air quality programme positively influencing government policy. But athlete health and the quality and safety of its events are the federation’s first priority.

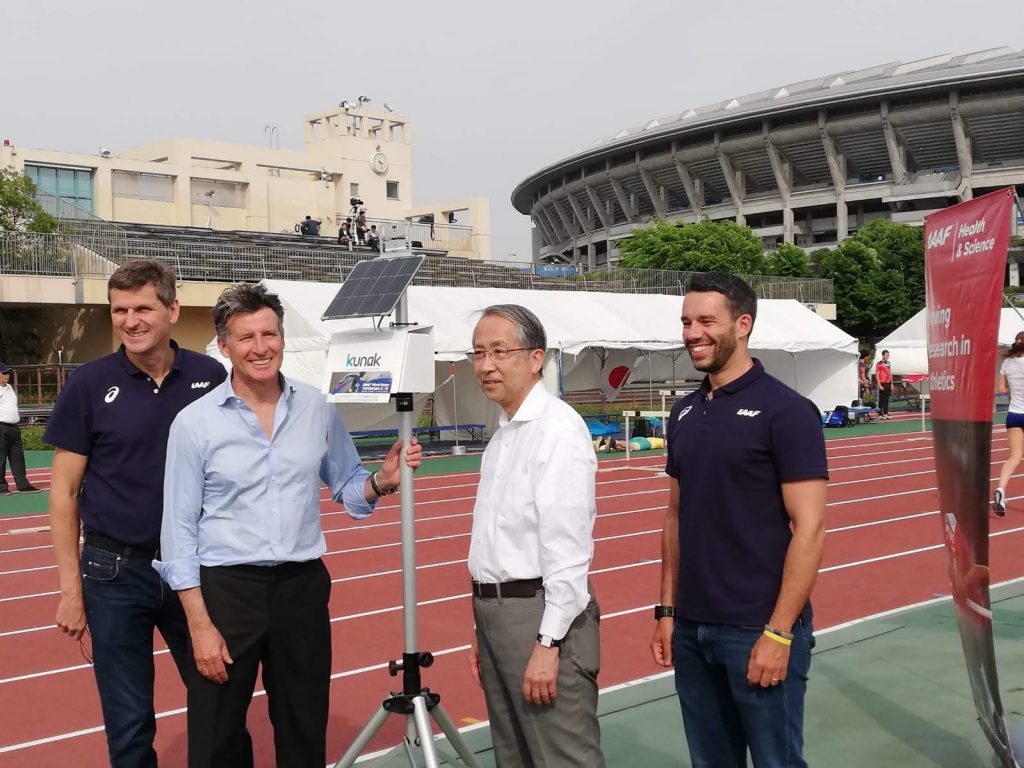

In May, the IAAF used its World Relays in Yokohama to record air quality at a live event for the first time. Air quality was measured ahead of the event, during the event and after the competition to compare air quality at different times.

Around 60 athletes were also asked to take a survey based on previously published scientific literature to find out about their perceptions of the air quality during their respective races and training routines. They were asked how air quality in Yokohama compared to the quality of air in the city or region they live and if they thought the air quality affected their performance.

Athletes with respiratory diseases, such as asthma, were also asked if the air aggravated their condition.

“The pilot was useful because we understood some of the limitations and how we can improve our approach in the future,” Adami explains. “What we will do in future events is look at more reliable clinical data. We won’t just be matching athlete performance to their perceptions of air quality, but also looking at the outcomes of medical encounters. We’ll be measuring how many athletes complain of respiratory stress, allergic reactions and other related conditions.”

Brock-Doyle adds that the IAAF has earmarked the World Indoor Championships in China in March 2020 and the World U20 Championships in Nairobi next summer as potential events to begin clinical trials related to air quality. But first, the organisation will review its 12-month pilot period, which ends in October.

“What we want to do is look at the results of our pilot, including the studies around stadium air quality, which will help us shape where we want to go,” Brock-Doyle says. “From the end of October we will analyse everything we’ve got and look at how we drive the project forward and in what areas.”

The IAAF will also use data collected during the pilot to strengthen partnerships with United Nations Environment, the World Health Organization (which is closely monitoring the correlation between air pollution, health and performance), and the United Nations Development Programme, which looks at the sustainable development of cities.

“One of the biggest issues is the reliability of data,” Brock-Doyle explains. “Lots of countries are recording it, but there are questions around transparency. A lot of people who want to talk to us about this project are interested in the fact that, working with Kunak, we’ve managed to adapt and develop something that is not only accurate and useful, but can also link to and be analysed against other data.

“We have a lot consider come November.”

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *